In 2015, the United Nations created the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with a promise to leave no one behind. Yet for the 1.1 billion people living with preventable blindness around the world – this promise immediately remains unfulfilled. As Director of Policy and Advocacy at The Fred Hollows Foundation, I’ve also come to realise that preventable blindness is not just a matter of inadequate eye health—it’s a critical global development issue. Eye health is increasingly recognised as integral to achieving numerous SDGs, including poverty reduction, economic growth, gender equality, and education. Consequently, the team and I at The Fred Hollows Foundation believe that it is high time that eye health is actively included as an indicator in the SDG framework.

The Foundation, started over 30 years ago by renowned ophthalmologist Professor Fred Hollows, alongside his friends and family, has long advocated for the inclusion of eye health in the global development agenda. Fred famously said: “It’s obscene to let people go blind when they don’t have to”. And I agree. It is a tragedy that in 2024 we have the know-how to address this issue with simple and cost effective solutions, yet 90% of cases in low and middle income countries mean that who you are, where you live and how much money you have dictates whether or not you can see.

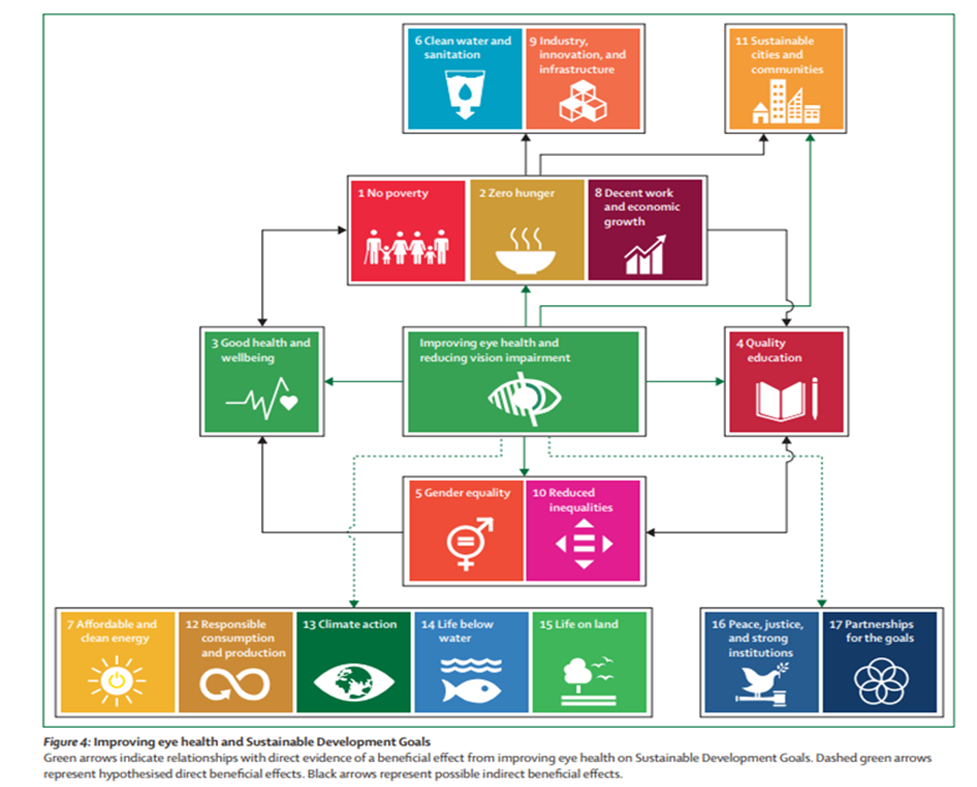

In 2021, the Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health undertook a series of systematic and scoping reviews to examine the relationship between eye health and the SDGs. Together, these reviews provided compelling evidence that improving access to eye health services will contribute to a range of SDGs. Additionally, it found that progress towards many SDGs will in turn benefit vision and eye health. This means that the relationship between eye health and the SDGs is actually two-way or a “win-win” strategy.

Image source: The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020

For example, the link between eye health and SDG 1: No Poverty is clear. People experiencing vision impairment may experience challenges maintaining employment. Treatable conditions, like cataracts, if left unaddressed, continue cycles of poverty. Lack of vision rehabilitation and access to assistive technologies, often means that people living with vision-related disability are locked out of education, work and cultural life.

Children with treatable vision loss can also face significant barriers to education – therefore undermining the achievement of SDG 4: Quality Education. In particular, vision impairment can delay learning and cognitive development. When vision loss goes untreated, it often forces an immediate family member to assume caregiving responsibilities, ultimately removing two people from education or the workforce. In contrast, restoring a child’s sight allows them to attend school, while their caregiver may return to work, bringing a positive impact on the family and community.

Investing in eye health also has far-reaching economic implications. A joint study by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) found that workers with vision impairments are 30% less likely to be employed. The study stressed the importance of protecting eye health in the workplace, as doing so would not only increase individual productivity and wellbeing but also contribute to national economic growth. Relatedly, in our own research, we have discovered that people who have had their sight restored through cataract surgery report levels of economic productivity and health-related quality of life on par with those without vision impairment (SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; and SDG 3: Good Health and Wellbeing). Six years after receiving treatment, many regain their economic footing and contribute meaningfully to their communities.

Research has also shown that addressing avoidable blindness is crucial to reducing gender inequality or achieving SDG 5: Gender Equality. Women are disproportionately affected by blindness and vision loss, partly due to social and economic barriers limiting their access to eye care. In many cultures, women are more likely to forego their own medical needs for the sake of their families, leaving their vision untreated. As a result, they experience higher rates of unemployment and dependency, perpetuating gender inequality. The Foundation has long worked to restore the sight of women, enabling them to re-enter the workforce, support their families, and participate in their communities.

However, despite the evidence, eye health was overlooked when the Sustainable Development Goals were formulated, and continues to be excluded from the SDG indicators. This was because eye health had traditionally been siloed as a vertical health intervention. Despite adoption of the United Nations General Assembly resolution 75/310 ‘Vision for Everyone’ accelerating action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals’ unanimously endorsed by 193 countries in 2021, the most recent opportunity to remedy this oversight was also missed. Earlier this year, the UN Inter-Agency Expert Group rejected two global eye health indicators on refractive error and cataract surgery for inclusion within the health related indicators, which were adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2021. And as the saying goes, if it’s not counted, it doesn’t count!

Including eye health as an indicator within the SDG framework would have provided crucial data and driven countries to prioritise eye health in their development agendas. Without this inclusion, governments are less likely to allocate budgetary resources, track data, or report on eye health progress. This oversight has consequences: by 2050, an estimated 1.7 billion people will experience avoidable blindness if current trends continue.

Fred Hollow’s program work in Bangladesh.

This means that we need to redouble our efforts to demonstrate how eye health is integrated across the SDGs. We already know that our eye health interventions, particularly cataract surgeries, are some of the most cost-effective health interventions, providing a return on average of $20.50USD for every $1USD invested.

At The Foundation, our consultative status with the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and working in coalition with sector partners and Member State champions, is one of the key ways that we are advocating for change. However, we can’t do this alone. We are calling on governments to step up. Governments, the private sector, UN institutions and community groups have a responsibility to do more to elevate eye health as a political priority and an imperative for sustainable development. This will require governments to prioritise eye health in policy and budgeting, for global organisations like the UN to incorporate eye health in their programs, and for communities to demand action.

In 2026, the first Global Eye Health Summit will be held, and we will be looking for concrete commitments from all actors to shift the momentum towards achieving eye care for all. Eye health belongs on the global development agenda, not only to honor the principle of leaving no one behind but also to leverage eye health as a driving force for sustainable change. I think if Fred knew that we still had 1.1 billion people living with avoidable blindness in 2024, he would be outraged. When we can do something about it, why wouldn’t we?

—————–

Brandon Ah Tong is the Director of Policy and Advocacy at The Fred Hollows Foundation. Brandon has 20 years of experience in policy and advocacy roles within the health, disability and international development sectors. He previously worked for the Australian peak body for eye health driving national policy reform in prevention and treatment, Indigenous eye care, disability and international development. Prior to that, he spent eight years advancing the human rights of people who are blind or have low vision, and was recognised with a Victorian Government award in 2014 for his leadership in disability advocacy. Brandon leads on multilateral advocacy to institutions such as WHO and United Nations and is a Board Director of Vision 2020 Australia.

Brandon Ah Tong is the Director of Policy and Advocacy at The Fred Hollows Foundation. Brandon has 20 years of experience in policy and advocacy roles within the health, disability and international development sectors. He previously worked for the Australian peak body for eye health driving national policy reform in prevention and treatment, Indigenous eye care, disability and international development. Prior to that, he spent eight years advancing the human rights of people who are blind or have low vision, and was recognised with a Victorian Government award in 2014 for his leadership in disability advocacy. Brandon leads on multilateral advocacy to institutions such as WHO and United Nations and is a Board Director of Vision 2020 Australia.

The Fred Hollows Foundation is an international development organisation working towards eliminating avoidable blindness and improving Indigenous Australian health.

Feature image: Ms Jarna has been a paramedic with non-profit organisation Paribar Kallyan Samity (PKS) in Jessore, Bangladesh, for five years. She plays an important role in providing medical care in around 2,000 homes and at makeshift clinics in the villages. In 2016, The Fred Hollows Foundation saw an opportunity to utilise the PKS’ network of maternal workers to deliver eye care services to local communities and provided the necessary training. In 2017, Jarna received eye care training from The Fred Hollows Foundation, enabling her to provide eye education, eye screening and the ability to identify issues that required attention at a properly equipped clinic. The Foundation’s innovation and initiative was acknowledged by French retailer L’Occitane, which awarded the Foundation’s Bangladesh team their annual Sight Award. They received a grant from The L’Occitane Foundation and with support from Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, maternal workers in 108 satellite clinics now offer eye care in the Khulna District.